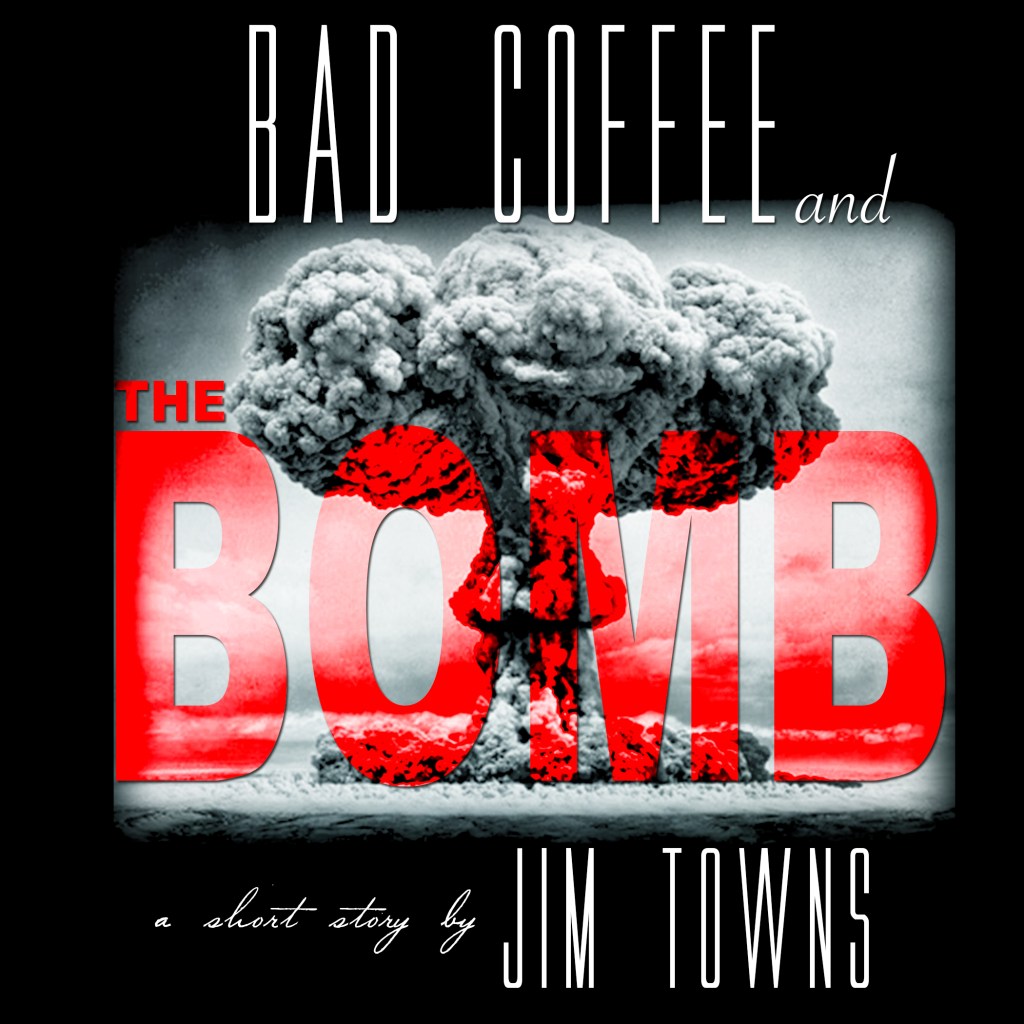

1.

1955.

It was snowing like hell and I was in the middle of Ohio, so that was two bad things. The snow had started the day after Thanksgiving and it hadn’t let up now for twenty-four hours. I’d gone to Toledo for a medical procedure, and was now on my way to Pittsburgh to conclude some long-outstanding business of a very personal nature- an easy five hours on any other day. But today was no ordinary damn day.

As the weak winter Sun lowered past the naked branches of trees lining the

interstate, and the snow continued to blow against the windshield of my Studebaker, the old familiar spidery tinge at the base of my spine started snaking its way northward up my backbone. This could be fine, or I could be in trouble. The whole thing was a tossup. I kept driving for a spell, taking the occasional sip of hot coffee from my thermos to help convince my eyes to stay open. I kept driving, and things kept getting worse. The highway was getting bad. They’d salted it, but the new snow was coming down too fast.

By the time I passed Elyria, the world around me was an inky black void beyond the halo of my headlights populated only with swirling, dancing white flakes, flakes which crashed over the glass in a constant barrage before skittering every which way. Every so often there would appear the occasional twin pinpoints of red tail lights ahead, which would slowly grow and grow until I’d pass some big truck taking it easy on the bad roads, or sometimes some poor family in a wood-paneled wagon, the father’s knuckles white on the wheel, his wife making the whole thing harder by hollering at him the whole time. The kids would be in the back, frightened like their parents or not caring at all, reading a comic book. Kids.

I’d take it easy passing them, so as not to startle the old geezer into jerking the wheel and killing his whole family. I didn’t need any more blood on my conscience than I already had. Once safely past them I’d push the engine a bit more. It was a good heavy car, the Studebaker. It held the road well. But the brakes were worn, and I knew I had to watch it. I’d meant to get them replaced, but I’d been busy with my work, lately. Now here I was.

Another ten miles and the flurries were coming down worse than ever. I’d had to slow way the hell down just to stay on the road and not steer off into the ditches on either side. This was getting ridiculous. If I slowed down any more I’d have to put the goddamn car in reverse. I passed a sign for an exit that advertised hot food, and my stomach did a little somersault. I was almost out of coffee, too. As the exit neared I turned the wheel to get off. Bad choice. The wheels on the car turned, but the car keep going. I tried to steer into the skid but the back end started slewing to the left. I tapped the breaks, nothing hard-but I may as well have not. The Studebaker started doing a lazy spin across the double lane. I saw trees pass before me, then the highway behind me, then more trees, then the exit ramp, then trees again until finally the Studebaker pirouetted to a gentle stop, sitting crosswise across two lanes of traffic.

Luckily for me the road was now all-but deserted. I took a breath and shook off the spiders that had crawled up the back of my neck. I had to get off the road before a car came. The Studebaker had stalled during the skid, and I pressed the starter to get it going again. It churned, and coughed, and that was about it. I pumped the gas pedal a bit to feed the engine and tried it again. Cough. Gurgle. Nothing.

Something in my periphery caught my eye. Far off down the road two white lights had appeared over a small crest. Alright then. Time to get moving. I could see the long graceful slope of the off ramp right in front of me, making its graceful way down the low embankment until it met the straight rural road below the interstate. Right there at the junction sat as cozy a little diner as you could want, its neon open sign glowing, roadweary sedans and trucks parked in the lot. I’d skidded out right at the exit. So close, just a

few feet.

I gave it a little more gas, careful not to flood the engine- and pressed the starter a third time. The engine gave a few turns this time. Good news, since the headlights down the road had now grown a helluva lot closer. I tried again but just got the same result. And again. Alright. The lights were starting to get awful near. This wasn’t working.

Out of habit I stuck my hand under the seat and pulled out the coal-black 1911A1, made sure the safety was on, and tucked it in my coat pocket before elbowing the door open. I put the shifter in neutral and got out into the freezing bluster. The lights were pretty damn close. I pushed on the door with all my might, and wound up with my bandaged face on the icy concrete as my shoes went out from under me. Beneath the car, I got a good look down the road. It was a truck that was coming- one of the big ones they

used for hauling goods cross-country. Even if the fella driving somehow saw me in all this blowing crud, there was no way he could bring something that size to a stop in time. Not on this ice. The truck’s radiator grille would be chromed steel. The idea of trying to put a bullet through its engine block to stop it was nothing more than fantasy, especially in this weather. So I got back up and pushed again, digging the heels of my shoes in as best I could. I pushed for what seemed like a real long time, and then a miracle- the

Studebaker’s wheels rolled maybe an inch. Then another. I dug in and pushed again.

Each inch was a bit more momentum to get her rolling. I didn’t look up for the truck anymore. Looking wasn’t gonna make the thing slow down any. A foot now, then another. Only ten more to go. The car was rolling good now. Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of my shadow stretching out across the asphalt, lit by the oncoming headlamps. I kept pushing. The sound of an air horn came out of the darkness. He’d seen me, but it was too late. I dug in and gave another heave and the Studebaker’s front tires slipped over the white line and onto the inclined pavement of the ramp. Gravity was on my side now. I kept pushing.

With a frigid gust of wind and a roar, the truck barreled behind me, missing the back bumper of the car by I don’t know how many inches. Probably not many. The sound faded and then the behemoth was swallowed by the night and gone like a phantom. The Studebaker was rolling on its own now. I hopped in before it could get away from me and closed the door. The heavy hunk of steel rolled down the hill in silence, a Flying Dutchman with me pumping on the breaks the whole way. There was a stop sign at the bottom where the ramp met the road but fortunately no one was coming as I sailed

through without stopping, bumping over the low curb of the diner’s lot and rolling to a gentle stop next to an old Packard.

I put the key in my pocket and glanced at the reflection of my face in the rearview mirror. This was going to be complicated. Maybe I could just wait out the storm in the car. By daybreak it would probably die down. But the car was dead, at least until I could look under the hood. That meant no heat, so after considering a moment I decided there really was no other option. I grabbed a scarf from the backseat, as well as a hat with a good wide brim, and did the best I could. A gust of polar air swept across the parking lot as I trotted to the diner, making the radio aerials of the cars whip back and forth. I took the four steps in two and grabbed the door handle and pulled.

2.

The warmth of the kitchen bathed the whole place. Its layout was a rectangle, with the kitchen occupying the top corner, leaving an L-shaped seating area to wrap around it. Several stools lined a high bar in front of the order window, and booths lined the rest. A bit of homey comfort for people on the road to seek refuge for a bit in the midst of their travels. Tonight the place was packed with them. A slender waitress whose name tag identified her as ‘Jill’ scurried around, snatching up plates from under the red heat lamps in the window and hustling them back and forth to her customers.

“Sit anywhere you can find, hon—we’re full-up tonight. Be with ya in a bit!” she called to me without looking. She looked frazzled. This was probably the busiest she’d been in a good long while. There weren’t a lot of options, which complicated matters.Every counter seat was taken, every booth had occupants. As I glanced around people would look up, then quickly lower their gaze when they got a good look at me. This had become the norm since my operation on Monday, and I’d become used to it.

I’d almost decided to tough it out in the car when an older man waved to me from the back corner of the diner. He caught my eye and waved again, motioning me over. I pulled my hat down and hurried towards him past averted eyes. He had a corner booth all to himself. He was smallish with what seemed like a larger-than-average head. That head was crowned by a thin layer of white hair, like cobwebs clinging to his scalp. His skin was tight over the cheekbones and jaw, sagging elsewhere. His old eyes had kept a bright cerulean color and were clear and sharp. His suit was old and well worn, the collar turned up at his neck despite the warmth from the

kitchen. I noticed the knot of his narrow tie was very small and pulled up tight below his bulging adam’s apple.

“Please, friend, sit here. Plenty of space.” His voice was scratchy but soft, and reminded me of two pieces of flannel rubbing against each other. I slid in on the side facing away from the rest of the diners, keeping the hat and scarf on, the coat buttoned, so as little of my face showed as possible.

“But you must be uncomfortable in all that….”

I shrugged. “I wouldn’t want to make you lose your appetite.” My own voice

sounded harsh and grating and too loud in my ears.

“Now don’t you worry about me. Besides, I’m done with my meal. Please,” he

gestured, and slowly I took off the hat and scarf and unbuttoned my coat, hunkering down low in the booth. He nodded to the bandages which covered my face: “Were you in an accident, friend?”

“No. I just had an operation…” I mumbled. Jill the waitress came by and filled up my coffee mug, freshening up the old man’s as well. She asked if she could get me anything from the kitchen and I ordered a medium steak with new potatoes and string beans off the menu. She was off without a second glance. She was busy and didn’t have time to be disgusted by the way I looked. I took a sip of coffee. Weak and burnt. I pulled a small flask of whiskey from my coat pocket (the one without the gun in it), keeping it

low. I offered the old man a drink but he held up his hand. I put a good slug into my coffee and put the flask away. The whiskey helped the coffee’s flavor significantly. After a moment it hit my stomach and warmth began spreading out from my core.

The old man and I sat and drank our coffees in silence for a few minutes, both of us staring at the whiteout beyond the windows. He shook his head.

“Helluva blow out there…”

“Yeah. Helluva blow.”

My steak came, still mooing. The potatoes reminded me of small rocks and the beans were barely solid, but I needed the energy so I dumped a bunch of salt and Heinz ketchup over the whole mess and wolfed the plate down before the taste could catch up with it.

“Been on the road long?” he asked me.

“From Toledo. Took me a few hours just to get this far. You?”

He smiled. “Oh, I’ve been traveling for quite some time now.”

“For work?” I asked. It seemed like a simple question. A straightforward one. But it made his brow wrinkle in thought.

“In a way, you could say so”, he replied. Cryptic. I didn’t deal in cryptic, so I let it drop, taking another gulp of the weak and bitter spiked brew.

“When I looked up and saw you, I thought maybe you’d just gotten back from the Korean conflict.”

“Too old. I was in the last one—briefly. Philippines and Okinawa, mostly. I sat this one out.” I glanced down at my watch, the one I’d bought on the street in Tokyo after the Surrender. Small kanji characters where the numbers would have been. It was still ticking, but I couldn’t remember the last time I’d wound it, so I did.

“And since then?” he asked. This was starting to get a little personal. Maybe the old man was just making the small talk, killing time—but I decided there’d been enough questions.

“Here and there. Nothing interesting to speak of. Say, you never said what you did for a living. Or are you retired?”

The old man gave out with a small chuckle. “Unfortunately I’m very much still active, Mr. Weyman.” He was seeing if I was paying attention. Of course I was. I hadn’t given him my name.

“Yes, I know who you are. Gregory Weyman. You’re wanted for homicide, among other things. You escaped from Carbon County Penitentiary, what, four months ago? Several guards lost their lives during that escape, if I’m correct. And several more of your associates have met similar fates in the intervening months. Been on a bit of a vendetta, haven’t we?”

I would have sensed a trap, if this had been a trap. And besides, there was no way anyone could have known I would stop at this godforsaken place in the middle of goddamn Ohio. No one could have predicted the storm. There were no cops waiting to pounce. Just regular, ordinary folk. Regular, except for this old man who knew way too much about me. He was sitting back, patiently letting me process all this. He seemed like he was

enjoying it.

“Yes, now we begin our real conversation.”

3.

I looked around, making sure no one nearby had overheard us. They hadn’t. They were all caught up inside their own tiny tragedies: a truck driver’s whose television parts weren’t going to be delivered on time. The teenaged couple, whose families were going to find out about their romance when they both missed curfew tonight. Some grandparents who weren’t going to make it to Akron in time to see their grandson’s school play. I looked back to the old man. He was just sitting there, staring at me. Not smiling, not frowning. No judgment or condemnation, no sympathy or sadness. Just an old man staring at me, maybe trying to gauge my response. My hand had automatically slipped into my coat pocket. My fingers were wrapped around the grip of the 1911, my thumb on

the safety release.

His eyes flicked down for the briefest second, and he spoke as if he could see through the table and my coat.

“You won’t need that, Mr. Weyman,” he said in his soft sandpaper voice. “I’m not the Law. I have no plans to arrest you and return you to Carbon County.”

I felt a wave like a rush of hot air wash over my face, and was aware of a strange stinging sensation in my cheeks. I was panicking, which of course was impossible because I didn’t panic. Ever. But my palms were moist, and my grip on the gun’s handle felt dangerously unsure. I hadn’t felt like this since…

“Steady,” he advised as he took another sip of the awful coffee. “Plenty of people here, not the type of place to start a shooting. Besides, I’m not armed. Doesn’t that conflict with some sort of gunman code of ethics?”

I stared him in the eye. “It never has before.”

He smiled at that. “Hmm,” was all he said. He wasn’t afraid, not nearly so much as I was rapidly realizing I was. This whole situation was upside down. I had to get hold of things.

“So just how do you know who I am?” I realized my other hand had gone up to the bandages.

“Changing your face is simply an external alteration, Mr. Weyman. You are still you. And no surgeon’s scalpel can change that.”

“That’s too bad, because I just paid a fella a whole lot of money to do this to me. And it was none too pleasant, let me tell you.”

“I can only imagine,” he replied. “Now please—we have a lot to talk about before dawn.” He was baiting me. Stalling for time, maybe. The spiders were back, crawling their ticklish way all over my neck. A random memory was trying to creep its way into my waking thoughts, spurred by something I’d mentioned earlier- but I pushed it back and gripped the gun butt tighter.

“Maybe you and I should go take a ride in your car and talk about this, old timer?”

He smiled. “Oh, I don’t have a car. I hitched a ride in Wheeling with that kind

gentleman.” He raised his mug a bit and the TV parts driver raised his back.

I had to regain control of the situation. Control was the key. Once you lost it, you weren’t easily going to get it back. My hand still clutched the automatic.

“Okay, here’s what’s gonna happen, old man. You and me are gonna get up together, and we’re going to walk out to my car…”

“You mean the one with the broken alternator?”

My next sentence died on my tongue. Things were going in a direction I was having difficulty following. The old man knew about my broken down car. Specifically he knew what was wrong with it, something I’d suspected, but wasn’t at all sure of.

“Just who the hell are you?”

“Oh, the answer to that would take much longer than we have tonight, son.”

“What happens tonight?”

“Not tonight,” he replied. “Tomorrow. At dawn.”

“Fine. Dawn. What happens at dawn? Is someone coming?”

He thought about it. “Is someone coming? I suppose you could say that, in a

metaphorical way… at the cost of being a bit prosaic, of course”

I released the safety, cocking the pistol. I’d heard enough, I told him. “Time to make sense, grandpa.”

“Very well, young man. By the time the Sun rises this morning, half the people on the face of the Earth will be incinerated.”

4.

He stared at me, daring me to laugh or to say something. I couldn’t really think of anything to say so I didn’t. So he continued:

“There will be no warning. The cold wave that’s blowing across the Midwest tonight will interrupt power and communications to several strategic missile silos to the west of here. There will be a test signal that will arrive garbled, and will not be able to be authenticated. Lacking the ability to confirm, a decision will be made by a junior officer to proceed with the launch. The target will be a top secret Russian submarine base in Balakava on the Black Sea. Upon discovery of the approaching Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile, the Soviet Union will launch thirty-seven R36-M2 missiles, and the United States will respond in kind. From that moment fifty percent of

the population of the World has only seventy-three minutes to live.”

“You’re insane, old timer.”

“Entirely possible. Unfortunately for all of us, that fact does not make what I know any less true.”

“What you’re saying hasn’t happened yet. You can’t be sure of something—”

“Which has not yet transpired?” He shook his large head. “You think of time like a school ruler: the days like marks along its edge. Time is not measured by marks on a line, son. I can see these things because I can see myself seeing them as they happen. I will be there. The fact that the version of me seeing these things when they occur is a future version of myself is irrelevant in the grander scheme. I am me, and the future me is also

me. The difference between the two is no more significant a change, than, say, using plastic surgery to alter one’s outer appearance.”

I sat there. I stared at him. He was crazy. I was stuck here in the middle of nowhere talking to a loony. A loony who somehow knew me, knew all about me- despite the bandages. My mind was working on the problem, but it was spinning its wheels. Nothing was making sense. Jill came by and refilled our coffees as the old man and I sat in silence, staring each other down. When she was gone I dumped the rest of the booze into mine. His eyes

watched my every move with the utmost interest. Finally he spoke again.

“When you were in the war, were you were there for the bombings? The two

cities..?”

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki. No, I wasn’t there. I was close enough.”

“Horrible things, these A-bombs… imagine the presumption, to take the very engine of creation—what makes the Sun shine, and to turn it into a weapon that kills thousands indiscriminately.”

“Those bombs kept me from having to storm the beaches of mainland Japan.”

“But at such a great human cost.”

“Wars aren’t won by good manners, old man.”

He looked at me. He looked through me. “But you saw, didn’t you… the aftermath… the fallout?”

The memory which had been fighting its way forward flashed before me and was gone in an instant. But the image lingered like spots after a flash photo. Charred figures, curled up around one another. Ash and bone and rubble and smoke. I tried to blink the vision away, turning to look all around us, at the living breathing souls in the diner, taking refuge from nature’s wrath for the night, then back at the old man. “Get out of my head, old man… you’re not welcome there…”

“Trust me, son, I’d just as soon not. It’s a very dark place,” he said. “But I need you to understand, if there’s any hope.”

“How can you know what you say is going to happen?” I asked, “Did you do

something..?”

He held up his wrinkled hand again. “Of course not… I have no involvement

whatsoever… how could I? But all the same I know it’s going to happen. Like I know your name, your past, your car problems… like I know that man sitting at the counter’s wife left him last month… like I know our waitress friend Jill got a letter today telling her she’s inherited a sizeable fortune from an aunt she never met, but she hasn’t gotten around to opening yet. I know all that, and I know the bombs will fall tomorrow morning.”

“Then you should call someone.”

“Such as?”

“I don’t know, NORAD or someone.”

“And tell them—?” He was right. He’d be written off as a crank, but they’d probably come by to round him up and lock him away, just to be safe. Meanwhile the missiles would be in the air. Christ, he had me believing this nonsense now.

“Why tell me all this? If the world’s gonna end, what possible point could there be in telling me about it with…” I looked again at the symbols on my watch- “four-and-a-half hours until it happens?”

The old man stared at me now for a very long time, as if trying to give me the opportunity to find the answer to my question on my own, but nothing came. The images of the people lying there blotted it all out. Images I’d been seeing every time I closed my eyes for the last seventeen years. Horror. Murder. An ocean of corpses stretching all the way to the horizon.

“And a line of them left in your path ever since…” he murmured. He’d been

eavesdropping on my thoughts again.

“I told you to get out of my goddamn head…” I snarled. I didn’t like how

completely unafraid the old man was of me. People usually found me much more intimidating, and I’d grown accustomed to it. I pulled the 1911 out of my pocket and laid it on the table. “Tell me why you’re telling me all this, or so help me I’ll put a bullet in your brain right here in front of everyone, old man.”

He smiled at that. He actually smiled. “Now Mr. Weyman, that wouldn’t be a very kind thing to do in front of all these innocent folk, now would it?” He paused, reflecting a moment, and began pushing his way out of the booth.

“Just where do you think you’re going?” I asked.

His eyes twinkled. “It’s gotten a bit stuffy in here, don’t you think? Perhaps a little stroll out in the winter air would be refreshing.” He stood up, stretching his old joints, “I wonder if you’d mind picking up the tab, though, friend? Very sorry, I seem to be a bit strapped at the moment.” And with that he

began strolling to the door.

I sat there for what seemed like a while but what was probably only seconds, staring at the bill sitting on face down on the Formica tabletop, its top corner boasting a circular stain where the old man had set his coffee cup down. I tucked the gun away, pulled out my billfold and dropped a tenner onto the table and got up to follow him out.

5.

It hadn’t let up any. The snow blew around in a cacophony of white flakes, blowing in my eyes, blowing up under my coat and threatening to tear my hat off my head. I turned my collar up more and shoved my hands deep inside my coat pockets, the right one keeping a stranglehold on the 1911.

He was walking a few yards in front of me, walking with a little shuffle, his knees stiff. He kept looking up at the Eastern sky, as though watching for the approaching light of dawn, racing against time as we crossed the edge of the paved parking surface and continued on into the fallow field behind, our shoes now crunching over the frozen ground.

He knew these things would happen because he could see himself seeing them, he’d said… it had taken me a while to figure out what he was implying by that. Maybe it had been the cold or the close call up on the interstate earlier, I was usually much faster on the uptake than this. But I was catching up now. If the old man couldn’t see himself seeing the bombs fall… if I took that future away from him…

We were probably a hundred yards away from the diner when he stopped. He didn’t turn. All around us the land went on and on and on, the level line of the horizon broken only by the occasional copse of trees or lonely barn.

The old man breathed in great lungfulls of frosty air, his exhalations blowing great white clouds, which immediately vanished into the blowing gale.

“Amazing, isn’t it? Even in the midst of all this barrenness… the darkest winter’s night, life bides its time underground, waiting for the thaw…”

His head half-turned to me, but his eyes avoided mine. “Together, perhaps we can guarantee there will be a thaw.”

The gun was heavy in my pocket. I could feel its metal growing colder by the minute out here in the night.

“Why me?”

“Because you are someone who can do this, son… none of them could.” He nodded back to the diner and I cast a glance over my shoulder. Its warm windows were all-but invisible, tiny squares of light far away. Far out of earshot of a handgun’s report. I turned back. The 1911 was out of my pocket. I released the safety and pulled the hammer back, the familiar metal click lost in the wind. We stood in quiet silence for a moment. Two men brought together by chance. Or at least what seemed like chance.

“Okay then. For what it’s worth… I’m sorry it has to be like this.”

“Is that something you usually say in this situation?”

“No.”

He shook his head. “Then maybe this, finally, is the beginning of something new for you, Gregory…”

“Maybe. Still, I’m damn sorry, old man.”

“Thank you,” he said. His eyes moved up to the sky to the east. “Well, we’d best be getting on with it, then, hadn’t we? Just to be sure…”

“Sure.” I raised the gun. The back of the old man’s head floated between the sights. “Hey old man?”

“Yes?”

The word almost caught in my throat.

“Thanks.”

He just nodded.

6.

The bandages were piled in a heap in the sink. I stared into the tarnished mirror of the diner’s restroom, and another man stared back at me. The doc had told me two weeks. It’d been six days. What did doctors know anyway?

It turned out the Doc had known what he was doing. The face I’d always known—its heavy brow, its jagged cheekbones, its thin lips—was gone. This new man had softer features, a warmer face. This was a relative’s face. A friend’s face. That was something different.

The snowstorm had begun blowing itself out now, and folk had started getting back on the road to wherever they were headed. Back out in the dining room I sat at one of the now-vacant barstools, sipping cup after cup of Jill’s terrible coffee. Each time she refilled my cup I found myself staring at her apron pocket, and the unopened letter sticking up out of it. I looked at my Tokyo watch for the hundredth time and finally got up. I didn’t leave her much of a tip. She wouldn’t need it.

It had stopped snowing. The sky was pale on the horizon and there were no

mushroom clouds to be seen. Had I managed to help save the world, by killing one old man? Or had I been suckered into believing the deranged ravings of a senile and suicidal fool? The fact that I’d never know began crawling its way down the back of my collar to join the rest of the spiders.

The Studebaker started up on the first try. I pulled out of the diner’s lot and onto the ramp, accelerating onto the highway. Soon I’d pass the State line and see the signs for Pittsburgh, with the unfinished business that was waiting for me there.

After a few miles, though, I started seeing the signs for Route 77 South. I’d never been to the South. I’d never seen the old manor houses with their big porches, or Spanish moss in the trees, or great mighty swamps filled with alligators. I’d never stood on the sandy shores of the Gulf of Mexico.

The wheels of the Studebaker seemed to steer themselves and the next thing I knew I was driving South.